Colorado’s above-average snowpack has an enemy: Out-of-state dust ~ The Colorado Sun

.

.

Fine soil from the Southwest is robbing the Colorado River of critical snowmelt. A scientist who monitors dust’s impact on snow wants state and federal leaders to take a closer look.

May 18, 2023

The story Susan Behery tells about dust blowing into Colorado from New Mexico and Arizona sounds almost Biblical, like cows dropping dead in their owners’ fields or swarms of locusts devouring their crops.

A hydraulic engineer for the Bureau of Reclamation in Durango, Behery says she once saw dirt falling from the sky in the manner of rain. It was so heavy, she said, it splatted when it hit the ground. When the storm that brought it moved on, a brown residue covered Behery’s car, her lawn furniture, her house. In fact, it covered the town of Durango, the town of Silverton and the San Juan Mountains, where Behery’s colleague, Jeff Derry, does the bulk of his work as the executive director and lead scientist for the Center for Snow and Avalanche Studies and its Dust on Snow program.

Behery says she and Derry work closely together. This time of year they talk by phone almost daily. That’s because Derry studies dust that travels to Colorado from northern New Mexico and Arizona. When it arrives here, in storms stopped short by the mountains, it settles in a distinct brown layer on the snow.

Derry’s main job is monitoring the dust layer (or layers) for water managers like Behery, because dust on snow is a major contributor to how much of the water in Colorado’s snowpack reaches the creeks, rivers and reservoirs that serve our state, and when the flows of those creeks and rivers reach their peak. That, in turn, impacts how Behery and her colleagues in water management control things like the levels of river water flowing into and out of reservoirs, of which Colorado has many.

The primary stem of the Colorado River has 15 dams and its tributaries have hundreds more. Each major tributary flows out of a river basin reliant on snow. “But we’ve been having these sporadic good precipitation years with lots of drought in between,” Behery says. And drought years lead to low snowpack, which, when coupled with dust, disrupts rivers.

When that happens, millions of people, animals and fish are directly impacted, says Behery. The vast majority don’t know it, Derry adds, but maybe they should.

According to a 2010 paper about the history of dust on snow by Thomas Painter, Jeffrey Deems and Jayne Belnap, climate models at that time predicted runoff losses of 7%-20% in this century due to human-induced climate warming.

Additionally, Derry says long-term trends based on data he has collected since 2003 show dust-on-snow is also wreaking havoc on flows in the Colorado River’s headwaters. But we can’t really stop dust from piling up on Colorado’s snowpack. And that’s a problem Derry says more people should know about.

Dust origination and politicization

The paper showing those haunting statistics about runoff losses also shows that by the late 1880s, decades prior to allocation of the Colorado River’s runoff between seven Western states in the 1920s, “a fivefold increase in dust loading from anthropologically disturbed soils in the southwest United States was decreasing snow albedo and shortening the duration of snow cover by several weeks.”

Understanding snow albedo takes some mental gymnastics. But as Derry puts it, when a dust layer settles on the snow, like a dark T-shirt, it absorbs the sun’s light and heat into the snowpack. And when the snow is free of dust, it reflects the light and heat back into the atmosphere. So high albedo leads to slower snowmelt and lower runoff, while low albedo leads to faster snowmelt and a higher runoff.

The paper also mentions dust shortening the duration of snow cover, and that’s a different process. Derry says as dust causes earlier snowmelt, plants and soil are exposed earlier in the spring. Increased exposure to the air and sun causes the soil to dry out through evapotranspiration, or the process by which water is transferred from the land to the atmosphere by evaporation from the soil and plants exhaling water vapor. “And that could have been water in the snow that would flow into streams,” he says.

The anthropologically disturbed soils of the 1800s and 1900s, however, were coming from poor farming techniques and vast numbers of cattle chewing up the landscape, Derry adds.

Jayne Belnap, a retired USGS soil ecologist with expertise in desert ecologies and grassland ecosystems, says those problems continue. “All low-elevation desert surfaces are stable until you disturb them,” she says. But when disturbance occurs —“by animals, bikes, cars, plows, feet,” she adds — the extremely fine soil that surfaces is perfect for flying on the wind to Colorado.

Desert surfaces aren’t naturally dusty places; they’ve just been grazed, plowed, recreated and prodded for oil and gas reserves to sandy soil devoid of nutrients, Belnap says. One solution to keep more soil intact is a change in government policy that holds whoever is degrading the soil accountable. Belnap says this includes anyone in the desert regions of northern New Mexico and Arizona who actively disturbs the protective surface of the desert. Derry adds that in the problem region, “there are a lot of federal land owners, and as far as I know, there’s no concerned effort to mitigate the problem.”

Then there’s the issue of liability, says Belnap.

“The soils between Tucson and Phoenix, which were plowed for cotton, went from coarse sand to silt. You can drive off the road, throw up a handful and it just hangs in the air,” she says. “When that’s disturbed, it blows across the highway and kills people. But in order to stabilize an area, the people in charge have to admit there’s a problem, and no one will. We finally got a congressman to get all upset about it, but if he says Joe rancher is creating a huge part of the problem, what’s Joe rancher gonna do? He’s gonna sue.”

What all of this amounts to, for now, at least, is people like Behery having to continue factoring dust into the way they manage Colorado water.

And in years like 2022, that meant being ready for some interesting flows.

Dust’s impact on Colorado’s water

In the spring of 2022, “the soil was ridiculously dry, the snowpack was terrible and windstorms blowing into Colorado from the south kicked all the dust up and deposited it all over our mountains,” Behery says.

That led to “snowpack running off early and in an extreme way, high-intensity, low-duration flows” and dropping river levels “that left us almost no base flows in the end of May-early June, when we had irrigation season coming online, which is when I have to release a lot of water,” she adds.

“So the severity of dust just really affects things. You never knew dirt could be so interesting, did you? People are like, ‘Dirt and dust. So icky.’”

But much rests on Behery’s releases of water from Navajo Reservoir, which spans the Colorado-New Mexico border southeast of Durango. Beneficiaries include endangered fish, which rely on certain flows to make it to their spawning grounds and to find food. Navajo Reservoir water also helps farmers downstream slake their crops and water their animals. And eventually, some flows into the San Juan River and on to the confluence with the Colorado River above Lake Powell, which with Lake Mead, serve millions of people who live in Arizona, Nevada and California.

That’s why Behery leans so heavily on Derry’s data from his main study site, in Senator Beck Basin, in the western San Juan Mountains between the towns of Silverton and Telluride.

Every winter through peak runoff since Derry took over the dust-on-snow study from his predecessor, Chris Landry, he has strapped on climbing skins and skied to the study site several times a week. Using a trusty shovel, a magnifying glass, a snow-water equivalent tube and a thermometer, he measures snow crystals, snow temperature and how much water the snowpack contains, before he checks the sensors of his backcountry climate station for albedo levels to provide an “albedo forecast.”

Since 2019, he has sent this information to Behery to indicate what she can expect to see downstream “in the next 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 30 days in the future,” he says.

The Center for Snow and Avalanche Studies is the only entity that monitors dust-on-snow conditions on an operational basis for the water community, researchers and stakeholders in the United States. The dust-on-snow program is a statewide effort, with 11 river basin monitoring sites from which Derry and a team of interns assess the density of dust on snow and report on local snowmelt and streamflow impacts to the corresponding watersheds.

Last year, with several major dust events, Derry’s data was especially prescient, Behery says. But this year isn’t so bad, “because we have a pretty wet situation in the Southwest. So even if we do have a lot of windstorms it probably won’t pick up as much dust in the past,” she adds.

But she’s still calling Derry, or he is calling her, daily or close to daily, and she’s using his data to help best predict peak flows. Water releases by Behery and other river managers from McPhee Reservoir on the Dolores River impact all of the normal stakeholders, plus Colorado’s boating and fishing communities. And Behery says for each type of release the hydrograph must have the “perfect shape.”

“For example, it needs higher flows (correlating to a different shape) on weekends when people are going to recreate,” she says. “The same goes for Memorial Day. And dust is always a part of the equation, because if it’s really dark and the sun is shining, we’ll have all of this runoff happening. And then we have a cool-down, and that will stop the runoff and we’ll think it has ended. But if you look at Jeff’s data, it hasn’t ended. There was just an inch of snow on top of the dust, which increased the snow’s albedo and slowed down the runoff. We’ll still have more coming, so we’ll know what to do with the boater spill. We can keep it coming. We don’t have to shut it off.”

But managing water like Behery does “is real-time fuzzy science,” she adds. “It’s what I call riding the dragon, because you’re just trying to stay on it. There are lots of decisions and lots of Monday morning quarterbacks.”

Behery’s water updates go out to 450 people,“internal, external, public, stakeholder and private,” she says. She coordinates with Derry to make the best-informed decisions. “Our goal is to make sure everyone is getting their fair share of water,” she adds. And this year is no different, although the snow is deeper, the temperatures cooler, the winds calmer and there’s less dust.

A dust scientist’s plea to Colorado senators

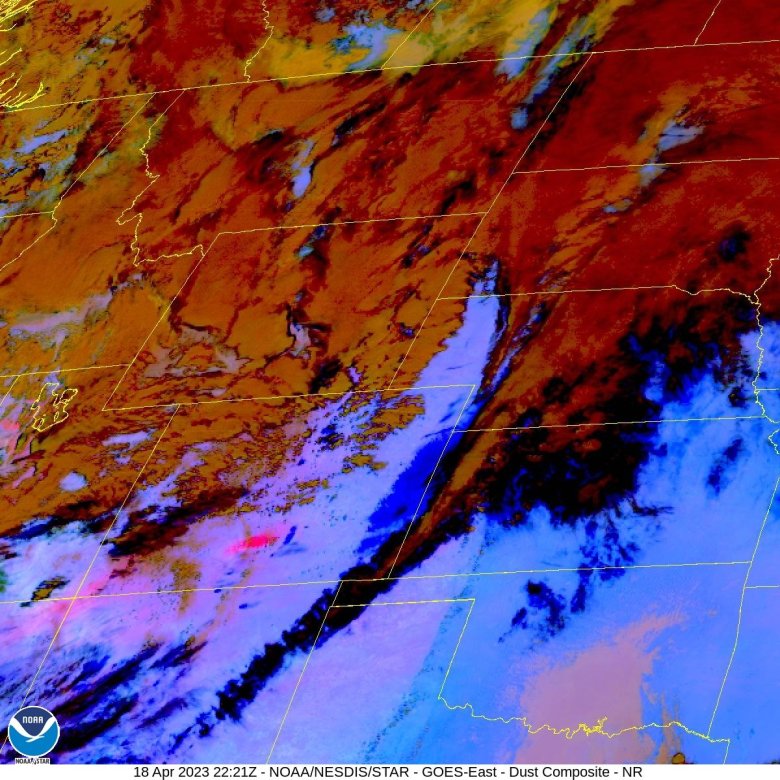

In fact, of the six Colorado dust events so far this season, the only major one occurred April 3.

Most of that event bypassed the Senator Beck study site and continued north, toward Aspen. There, at Grand Mesa and at Beaver Creek, people reported seeing a “gritty, dark layer” that even after new snow had covered it, skiers’ tracks resurfaced. But in Derry’s dust-on-snow update for April 6, he wrote, “I guess we all knew [a significant event] would happen eventually.”

Opinion: The Colorado River drought contingency plan is no longer a contingency

Half of the western U.S. is out of drought, but not fully recovered

The event turned out to be widespread and nasty in terms of the amount of dust deposited on a relatively pristine snowpack that had essentially reached maximum accumulation, he reported. “It just takes one bad dust event to change things — this one will change the characteristics of snowmelt and runoff for the duration of spring dramatically.” The dust put places that received it in the “average” category.

But in the San Juan basin, which Behery manages, even given this event, things are looking a little better than normal.

“In a year like this where we have a good snowpack, the dust cycle continues but we can have a reset,” she says. “Still, we need subsequent years of snowpack and runoff that are either average or above average to make a lasting impact. People think one year can do it, but we’ve had 20 years of drought with a few little good years in between.”

Derry told The Sun that he’s part of a “small, loose group” of scientists, landowners, land managers and others working to build a coalition that can define the problem with and potential solutions for dust and then encourage those who own the lands dust originates on — including the BLM and Bureau of Indian Affairs — to take action through policy and support. His motivation for helping start the coalition “is when I give talks to groups — doesn’t matter who — and explain what I do, always, the first question I get is, ‘We know what the problem is, why don’t we fix it?’ And I am like, ‘Yeah, why don’t we?’ so this is my attempt.”

At the end of his April 6 update, he also addressed Sens. John Hickenlooper and Michael Bennet, who were traveling through Colorado with senators from other Colorado River Basin states to see and discuss river issues and solutions. “It would be valuable if the group were to swing through the Southern Colorado Plateau and discuss the imperative need to restore soil health for the benefit of the land itself, the quality of life and livelihood of the people who live in the region, and of course to minimize dust transport to the Colorado snowpack,” Derry wrote.

The Decade That Cannot Be Deleted ~ NYT

.

Alamy Photo

.

By Pamela Paul

Opinion Columnist

It would seem impossible to forget or minimize the Cultural Revolution in China, which lasted from 1966 to 1976, resulted in an estimated 1.6 million to two million deaths and scarred a generation and its descendants. The movement, which under Mao Zedong’s leadership sought to purge Chinese society of all remaining non-Communist elements, upended nearly every hallowed institution and custom. Teachers and schools long held in esteem were denounced. Books were burned and banned, museums ransacked, private art collections destroyed. Intellectuals were tortured.

But in China, a country where information is often suppressed and history is constantly rewritten — witness recent government censorship of Covid research and the obscuring of Hong Kong’s British colonial past in new school textbooks — the memory of the Cultural Revolution risks being forgotten, sanitized and abused, to the detriment of the nation’s future.

The Chinese government has never been particularly eager to preserve the memory of that sordid decade. When I spent six weeks traveling in China in 1994 — a slightly more open time in the country — I encountered few public acknowledgments of the Cultural Revolution. Museum placards and catalogs often simply skipped a decade in their timelines or provided brief references in the passive voice along the lines of “historical events that took place.”

But in her new book, “Red Memory: The Afterlives of China’s Cultural Revolution,” the journalist Tania Branigan notes that under Xi Jinping, China’s top leader, efforts to suppress this history have intensified — with troubling implications for the political health of the country at a time when it looms larger than ever on the world stage. “When you’ve had a collective trauma, you really need a collective response,” Branigan told me recently. “I can see why the Communist Party wants to avoid the rancor and bitterness, but when you don’t have that kind of acknowledgment, you can move on — but you can’t really recover.”

DENNIS HOPPER’S MAD VISION ~ ESQUIRE

.

The actor-director’s follow-up to Easy Rider was going to change Hollywood. That is, if he could get the damn thing made.

BY JOSH KARP

OCT 1, 2018

Courtesy of Areblos Films

Henry Fonda wasn’t holding back. Not even a little.

It was October 1970, and the 65-year old Hollywood legend had recently watched his son Peter on The David Frost Show.

Peter wasn’t the problem. Fonda’s son had come out, shaken Frost’s hand, and taken his seat—like a goddamn normal person. No, the thing raising Fonda’s blood pressure was what happened next, when Peter’s friend, Dennis Hopper came on stage.

“Dennis came out floating,” Fonda later told a New York Times reporter. He demonstrated what he meant by flouncing about the living room of his Manhattan apartment with arms spread wide and head tossed backwards. “And every time Frost asked him a question, he began giggling… Dennis is stoned out of his mind. He’d have to be to act that way.”

“Put that in your story,” Fonda told the reporter. ‘This is not off the record. Dennis Hopper is an idiot. Spell that name right D-e-n-n-i-s H-o-p-p-e-r!”

Reached at his home in Taos, New Mexico, Hopper laughed when told about Fonda’s rant. “Henry Fonda said I was an idiot?” Hopper said. “Well, I guess it goes to show you what the establishment view of me is.”

Courtesy of Areblos Films

Hopper could afford to be amused. After years of being regarded by much of the old guard as an ill-mannered, drug-addled lunatic, he was now possibly the hottest filmmaker in Hollywood. Easy Rider, which Hopper had made for less than half a million dollars, was the surprise smash of 1969, grossing $60 million and seemingly striking a death blow to the studio system that nourished the elder Fonda.

Hopper’s overnight transformation from unemployable fuckup to Wellesian genius was made exponentially more aggravating when Universal gave him total control over his next picture, on which he was currently in post-production: The Last Movie, which Hopper wrote, directed, starred in, and edited. He declared it “the first American art film.”

Hopper was keenly aware that the project would determine the course of his future, as he told the endless stream of reporters who visited him on the film’s set. “The Last Movie is the big one,” he told one writer. “If I foul up now, they’ll say Easy Rider was a fluke. But, I’ve got to take chances to do what I want.”

And, true to his word, that’s exactly what he did.

HOLLYWOOD, 1965-1969

The idea for The Last Movie came to Hopper in 1965 at a wrap party for the John Wayne film The Sons of Katie Elder in Durango, Mexico, a popular location for Hollywood westerns.

Katie Elder was Hopper’s first Hollywood movie since the 1958 western From Hell to Texas, also directed by Henry Hathaway, who had effectively blacklisted the actor after his Method approach slowed down production. Things came to a head one night when Hopper turned the set into his own personal Actor’s Studio, trying every possible approach other than Hathaway’s for eighty-five takes before bursting into tears of frustration and begging the director to give him his line readings one last time. When they were done, Hathaway threw an arm around Hopper and said, “Kid, you’ll never work in this town again.”

Courtesy of Areblos Films

For the next six years, Hopper didn’t appear in a single Hollywood film and struggled to find work even in television. But in late 1964, Hathaway and Wayne decided that the 28-year-old actor—who was then married to Brooke Hayward, the scion of a prominent Hollywood family, and had a young daughter to support—had suffered enough.

On his best behavior throughout the Katie Elder shoot, Hopper became fast friends with 22-year old actor Michael Anderson Jr. “We were the only two people under 100,” Anderson said. When the film wrapped, Hopper and Anderson attended a party thrown by a stuntman who’d rented a house in Durango. They spent the evening smoking pot and staring into an outdoor fireplace in relative silence, until Hopper turned to Anderson and said, “Hey man, I just had the best idea for a movie. It’s about making movies and the effect it has on people, and what they do when a movie company leaves town.”

Hopper teamed up with screenwriter Stewart Stern. Stern’s personal papers—containing everything from his high school academic records, correspondence with Joan Crawford and Paul Newman, and scripts for pictures like Rebel Without a Cause, his best-known movie (and Hopper’s film acting debut)—make up 22 boxes located in a special collections library at the University of Iowa. For years, only one of those boxes was unavailable for public view: Box 22, which contained the materials for The Last Movieand was placed under seal until after both Hopper and Stern were dead. Its contents tell a portion of the story of Stern’s collaboration with Hopper, which began when Hopper returned to Los Angeles and settled in at Stern’s house to write a treatment for what they were calling The Last Movie, or Boo Hoo in Tinseltown.

“Dennis would stride back and forth in the room and we’d spitball ideas,” Stern said. “I sat at the typewriter and he’d walk behind me with his joint and he’d be raving, ‘I bet you could really write if you had a little joint.’ I said, ‘Well I just won’t do it, it makes me hallucinate.’ So he said, ‘There’s something called a bong, you just inhale it over water.’”

As Hopper blew smoke down the snorkel of Stern’s scuba mask, the pair wrote a 98-page outline for the story of a broken-down stuntman named Tex who shacks up with an indigenous girl and stays behind in a small Latin American town where a western has just wrapped. After watching the film company shoot their western, the natives begin to reenact its making as a religious ritual using the old sets, as well as cameras and other equipment they’ve made out of sticks. Tex, meanwhile, plans to seek his fortune by developing the town as a location for future productions. “He’s Mr. Middle America,” Hopper said. “He dreams of big cars, swimming pools, gorgeous girls. He’s so innocent he doesn’t realize he’s living out a myth. Nailing himself to a cross of gold.” The natives, however, do understand, and create a passion play of “greed and violence” using Tex as the doomed Christ figure in their deadly ceremony.

“The end,” Hopper said, “is far out.”

~~~

.

Showing this week: ‘Blue Velvet

FRANK BOOTH IS A TWISTED MF … rŌbert

.

Rated R for for strong violent and disturbing content, some graphic nudity and pervasive language.

On Dennis Hopper’s birthday Wednesday (May 17), the Rebel Film Festival, Taos Center for the Arts, and Hopper Reserve present a free screening of David Lynch’s 1986 classic surreal mystery. Festivities begin at 6 p.m. with food vendors and Hopper’s commemoration birthday cake celebration.

The film begins with a young college student named Jeffrey Beaumont (Kyle MacLachlan) who finds a severed ear near his home in the quiet town of Lumberton where he helps out at his father’s hardware store. Jeffrey is puzzled when the cops take the ear but brush him off as they investigate.

Intrigued, especially after befriending the cop’s teenage daughter, Sandy (Laura Dern), Jeffrey decides to find out more when Sandy, in an overheard conversation at home, learns that the ear has something to do with a nightclub singer named Dorothy Valens (Isabella Rossellini). From there the story takes a strange turn, very strange, especially after Jeffrey decides to sneak into Dorothy’s apartment.

While Jeffrey hides in a closet, he witnesses a visit by Frank Booth (Dennis Hopper.). This performance hit new levels of depravity, even for Hopper who was already well known for pushing the envelope while depicting cinematic oddity. Be forewarned: this scene includes extremely difficult to watch sexual violence.

According to imdb.com, several of the actors who were considered for the role of Frank found the character too repulsive and intense. Hopper, by contrast, is reported to have exclaimed, “I’ve got to play Frank. Because I am Frank!”

Hopper and co-star Dean Stockwell, who both lived in Taos, offer performances that are truly memorable. Highly recommended. However, this film, while edgy in an artistic sense, is designed to confront psycho-sexual norms, while creating some of the most suspenseful visuals ever filmed.

WESTERN STATES NEAR HISTORIC DEAL TO PROTECT COLORADO RIVER ~ The Washington Post

States and Interior Department are still wrestling over process, compensation for conserving a river that sustains millions

May 17, 2023

After nearly a year wrestling over the fate of their water supply, California, Arizona and Nevada — the three key states in the Colorado River’s current crisis — have coalesced around a plan to voluntarily conserve a major portion of their river water in exchange for more than $1 billion in federal funds, according to people familiar with the negotiations.

The consensus emerging among these states and the Biden administration aims to conserve about 13 percent of their allocation of river water over the next three years and protect the nation’s largest reservoirs, which provide drinking water and hydropower for tens of millions of people.

But thorny issues remain that could complicate a deal. The parties are trying to work through them before a key deadline at the end of the month, according to several current and former state and federal officials familiar with the situation.

Participants are discussing cutting back about 3 million acre-feet of water over the next three years, the majority of it paid for with federal money approved in the Inflation Reduction Act. But the parties are still negotiating how much of those water savings will go uncompensated. In meetings over the last month, representatives for the three states, which form the river’s Lower Basin, have also raised doubts about the federal government’s environmental review process that is now underway to formally revise the rules that govern operations at Lake Powell and Lake Mead.

State officials have suggested they could make a deal on their own and are resisting a May 30 deadline to comment on the alternatives the federal government has laid out in that process, according to people familiar with the talks. The review process is intended to define Interior Secretary Deb Haaland’s authority to make emergency cuts in states’ water use, even if those cuts contradict existing water rights.

These developments represent a new phase in the long-running talks about the future of the river. For much of the past year, negotiations have pitted California against Arizona, as they are the states who suck the most from Lake Mead and will have to bear the greatest burden of the historic cuts that the Biden administration has been calling for to protect the river. But these states now appear more united than ever and are closing their differences with the federal government, even as significant issues remain unresolved.

The Interior Department declined to comment on the status of the private negotiations. The Colorado River commissioners from Arizona, California and Nevada also declined to comment.

The Colorado River runs through seven states and supplies more than 40 million people with water, and is a major resource for agriculture in the western U.S. But the river has been drying up for decades, and water levels in Lake Powell and Lake Mead — both reservoirs on the river — hit historic lows in the past year.

A combination of chronic water overuse and historic drought, accelerated by a warming climate, is draining the river. Snow has been abundant in California this year, and while the snowpack helps replenish the reservoirs, it won’t solve the Colorado River crisis or reverse the effects of a 23-year drought.

What’s being done to save the Colorado River?

It’s complicated. States could agree to cut back on their water use, or the federal government could step in. But cuts could affect the farming regions that keep supermarkets stocked with fresh produce in the winter months, or populations of cities like Phoenix and Los Angeles, or both. But if nothing is done, experts fear that the impact could be even worse.

Some water authorities in the West want to ensure that any deal that emerges would entail binding commitments among the Lower Basin states, which draw from Lake Mead and consume more of the river each year than the states of the Upper Basin: Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming.

“We want to support the Lower Basin if they have significant additional reductions, verifiable, binding and enforceable,” said Becky Mitchell, Colorado’s commissioner for the negotiations. “Are we going to make a choice to do better? If we don’t want the secretary to manage us, can we show we can manage ourselves?”

The Colorado River runs 1,450 miles from the Rocky Mountains to Mexico and is a vital lifeline for cities and farms throughout the West. But climate change has made the region hotter and drier, and exposed how rules made over a century ago to share the river among Western states are inadequate to keep it from drying up.

In June, with Lake Mead and Lake Powell about a quarter full and nearing levels where the hydroelectric dams could no longer produce power, U.S. Bureau of Reclamation Commissioner Camille Calimlim Touton testified before the Senate that states needed to stop using 2 to 4 million acre-feet of water — up to one-third of the entire average annual flow — or the federal government would step in to protect the river.

Utah’s Suicide Pact With the Fossil Fuel Industry ~ Mother Jones

.

The state’s fixation on oil and gas development threatens the Colorado River watershed.

MAY 4, 2023

The White River in Northeastern Utah emerges from the Colorado mountains into the Uinta Basin. Russel Albert Daniels

The GPS coordinates weren’t especially helpful last May as we drove across the remote Tavaputs Plateau in Utah’s Uinta Basin. Cell service was spotty in the vast expanse of land crosshatched with unpaved roads identified on the map only as “Well Road 4304735551” or “Chevron Pipeline Road.” Photographer Russel Albert Daniels and I had set off that morning from Vernal (population 10,241), in search of a 15-square-mile plot of undeveloped land purchased in 2011 by the Estonian-government-owned energy company Enefit.

On that land, the Estonians had hoped to create the first commercial-scale oil shale mining and processing facility in the United States, with a 320-acre industrial plant that would process 28 million tons of strip-mined shale and turn it into 50,000 barrels of oil every day for 30 years. Rich with traditional oil and gas reserves, the Uinta Basin also sits atop the largest oil shale reserve in the world, a 6 million-year-old geologic formation where Utah officials estimate a tantalizing 77 billion barrels of potentially recoverable oil lie just waiting to be exploited.

At a public meeting back in 2013, former Rep. Rob Bishop (R-Utah) told the Deseret News that the “exciting” Enefit project “has the potential to create significant revenue and jobs here in Utah and help with energy independence nationwide.” Cody Stewart, an energy adviser to former Governor Gary Herbert, called it “a game changer” with “the potential to make Utah a significant player on the energy map.”

The prognosis was not quite as bright in Estonia. Two years after the purchase, Estonian parliament members warned that the government risked losing $100 million on the deal because early lab tests in Germany had failed to affordably produce oil from Utah’s shale. Ingo Valgma, director of the mining department at the Tallinn University of Technology, told an Estonian journalist that the technology for producing oil in Utah was not a few years away but decades. Nonetheless, the Estonians stayed put and Utah’s elected officials sallied forth, optimistically insisting that oil shale riches were just around the corner.

As Russel and I bumped along the dirt roads of eastern Utah in search of Enefit’s land, it became painfully obvious that the Estonians had overlooked a major problem when they plunked down $42 million to acquire 30,000 acres of sagebrush in the basin: water, or the lack of it. Pulling a single barrel of oil out of shale requires between two and four barrels of water. The Uinta Basin lies within an arid, desert climate that averages about 8 inches of rain annually at the wettest of times. What little it does have comes from the critical watershed of the dying Colorado River, which more than 40 million people in the West rely on for agriculture and drinking water.

Enefit’s land sits just 40 miles from where the White River meets the Green, the largest and most important tributary of the Colorado River. To mine and process oil shale, Enefit hoped to suck as much as 11,000-acre-feet of water out of the Green River every year—about 10 million gallons a day, or enough to supply the daily needs of 90,000 households downstream in Arizona. (An acre-foot equals about 326,000 gallons or enough to cover about a football field with a foot of water.) Unfortunately, perhaps, for Enefit, “That water, more than likely, doesn’t exist,” says Brad Udall, a senior water and climate research scientist at Colorado State University’s Colorado Water Center.

Last summer, during one of the driest years of a 23-year mega drought in the West, the federal government told the seven Colorado River basin states they must come up with a plan to reduce water consumption by up to 40 percent of the river’s current volume, or enough to serve more than 6 million households for a year. This year, federal water managers plan to cut deliveries from the river by up to 25 percent. Record snowfall this winter may head off some of the worst of the cuts, but the runoff will only partially refill badly depleted Lake Powell and Lake Mead, the country’s largest reservoirs. The water crisis remains urgent, and the long-term prospects for the Colorado are grim.

The dire state of the Colorado River hasn’t stopped Utah officials from enthusiastically supporting policies to encourage Enefit’s oil shale production and all sorts of other thirsty, ill-conceived fossil fuel projects in the Uinta Basin in what some environmentalists have dubbed a “suicide pact.” These projects and priorities generally, and Enefit’s in particular, illustrate how a state, run largely by people who don’t believe in climate change, still presses ahead with carbon-belching fossil-fuel developments that, if successful, will only exacerbate the megadrought that has brought the Colorado River—and the West—to the brink of disaster.“I’ve given talks to high-level people in Utah who refuse to acknowledge the relationship between climate change and the drought and the American West.”

“The whole connection between water and climate change, and conventional energy development and climate change, is not front and center” in Utah, says Udall. “I’ve given talks to high-level people in Utah who refuse to acknowledge the relationship between climate change and the drought and the American West.”

In 1861, LDS church president Brigham Young assembled a group of missionaries in Salt Lake City and ordered them to set off for the Uinta Basin to create new Mormon settlements in the region—lest the “Gentiles” get there first. A few months later, the scouting party reported back gloomily that the basin was “one vast contiguity of waste, and measurably valueless, excepting for nomadic purposes, hunting grounds for Indians, and to hold the world together.” Young suggested to President Abraham Lincoln that he use the wasteland for a Ute tribe reservation—and that’s what happened.

About 20 years later, however, a white settler named Mike Callahan built a new cabin just over the border in Colorado next to Parachute Creek. He used pretty, local rocks for his fireplace and chimney. Legend has it that the first time he lit a fire on the hearth, the cabin burned down. The pretty rocks turned out to be flammable oil shale. Ever since, speculators have been trying to figure out how to monetize those massive shale deposits in Utah. Still, it wasn’t until the oil shocks of the 1970s that the federal government got involved.

In 1974, the Department of Interior leased two large parcels of public land in the Uinta Basin that Enefit now controls to a consortium of oil companies that became the White River Shale Company. The Carter administration created loan subsidies and other supports to encourage oil shale mining, and construction began on a coal-fired power plant to support the future industry. In 1982, the White River Shale company pledged to invest $100 million into the operation and began the construction of a new mine in the basin.

Just three years later, global oil prices collapsed, Ronald Reagan cut off federal subsidies for alternative fuel development, and the company officially abandoned the mine. But in 2005, Congress passed a bill pushed by President George W. Bush and Utah Republican senators Orrin Hatch and Robert Bennett that declared oil shale an “important domestic resource” for national security and directed the federal government to accelerate its development.”We are committed to being in the oil shale business for years and years to come.”

The US Bureau of Land Management moved to reopen the mine in 2006 and leased the 160-acre site to a company backed by an Alabama coal firm called Oil Shale Exploration to conduct research on oil shale processing. “We are committed to being in the oil shale business for years and years to come,” promised managing partner Dan Elcan at the time. The company lasted five years. In 2011, Enefit bought all the defunct company’s assets, including the White River mine lease and 30,000 acres of private land nearby where it planned to open a shale processing plant.

1st day of garden school

DOUG RUSHKOFF IS READY TO RENOUNCE THE DIGITAL REVOLUTION ~ WIRED

.

PHOTOGRAPH: CLARK HODGIN

The former techno-optimist has taken a decisive political left turn. He says it’s the only human option

THE MEDIA STUDIES building at Queens College is small and dark, with low ceilings and narrow corridors. It was built more than a century ago as a residential school for incorrigible boys, and a certain atmosphere of neglect remains. When I visit on a January weekday to see Douglas Rushkoff, who teaches here, he guides me around a stack of fallen ceiling tiles to his office in a back corner of the first floor. The Wi-Fi in the room is spotty, so he uses an Ethernet adapter to plug his laptop into the wall. The only evidence that we haven’t traveled back to the ’90s is that when it’s time for class, no students show up. Instead, Rushkoff opens his laptop and brings up a grid of faceless black boxes.

This is the first course meeting of “Digital Economics: Crypto, NFTs and the Blockchain.” Rushkoff is a good sport about teaching on Zoom, though it’s a shame his class of mostly undergraduates can’t fully appreciate the 62-year-old media-studies-professor look that he’s absolutely nailed: black V-neck, cropped gray hair. He launches into an impassioned half-hour lecture in which he urges his students, only three of whom have their cameras on, to see through the social construction of money—he pulls out a dollar bill and waves it in front of the laptop screen, saying, “This is not money. This is a piece of paper that we use to represent money”—and to probe what he calls the “big question” of his life’s work: how power travels across media landscapes.

Outside of this Queens College classroom, Rushkoff is a widely cited theorist of the internet, known for his prolific and influential writings on culture and economics. He gets the occasional student who recognizes his work—“He’s a famous author,” one writes on Rate My Professor, “just do a Google search”—but most of them are busy people logging in to class from their phones, more interested in fulfilling their degree requirements than in the dense collage of Rushkoff’s book covers taped to the wall behind his desk.

That his class may not be his students’ first priority doesn’t bother Rushkoff much. He’s made a point of landing at City University of New York in Queens after a teaching stint at the far more expensive, prestige-mongering, private New York University. In a portion of his lecture, he hints at the trajectory his intellectual life has taken:

“I was pretty freaking excited in the ’90s about the possibilities for a new kind of peer-to-peer economy. What we would build that would be like a TOR network of economics, the great Napsterization of economics in a digital environment,” he tells his students. But more recently, he continues, he’s turned his attention to something else that this new digital economy has created: “It made a bunch of billionaires and a whole lot of really poor, unhappy people.”

This kind of rhetoric is part of a recent, decisive shift in direction for Rushkoff. For the past 30 years, across more than a dozen nonfiction books, innumerable articles, and various media projects about the state of society in the internet age, Rushkoff had always walked a tightrope between optimism and skepticism. He was one of the original enthusiasts of technology’s prosocial potential, charting a path through the digital landscape for those who shared his renegade, anti-government spirit. As Silicon Valley shed its cyberpunk soul and devolved into an incubator of corporate greed, he continued to advocate for his values from within. Until now. Last fall, with the publication of his latest book, Survival of the Richest: Escape Fantasies of the Tech Billionaires, Rushkoff all but officially renounced his membership in the guild of spokespeople for the digital revolution. So what happened?

It is, generally speaking, a difficult time to maintain a straight face as a diehard advocate of decentralization. A couple of months before I come to see Rushkoff, the cryptocurrency exchange FTX, run by a cabal of tasteless pyramid schemers blathering platitudes about art and community, collapsed, torching billions of dollars in the process. These internet capitalists proved to be worse guardians of the public interest than even the corporate robber barons of yore. (Some weeks after my visit, Silicon Valley Bank failed and nearly dragged the global financial system down along with it—a direct result of the Trump administration’s deregulation agenda.)

Confronted with such irrefutable evidence, Rushkoff isn’t just lying low or changing the subject the way perennial techno-optimists often do. His conversion is deeper. “I find, a lot of times, digital technologies are really good at exacerbating the problem while also camouflaging the problem,” he tells the black boxes that represent his students. “They make things worse while making it look like something’s actually changed.” Still, as he talks, I can occasionally catch a glimpse of Rushkoff reverting into his former persona: the inveterate Gen X techno-optimist, the man who can’t resist the untested promise of ever newer tools. Near the end of class, he starts instructing his students to not use ChatGPT to write their assignments, then halts abruptly, as if unable to go on. “Well, actually,” he says, reconsidering, “we’ll figure it out.”

Lisbon Valley mining land rush continues ~ The Land Desk

Get a subscription, don’t be a cheap bastard.. Thompson is one of the best muckrakers in the west …

Australian company hypes its proposed Utah Lithium Project

| JONATHAN P. THOMPSON MAY 16 . |

Mining Monitor

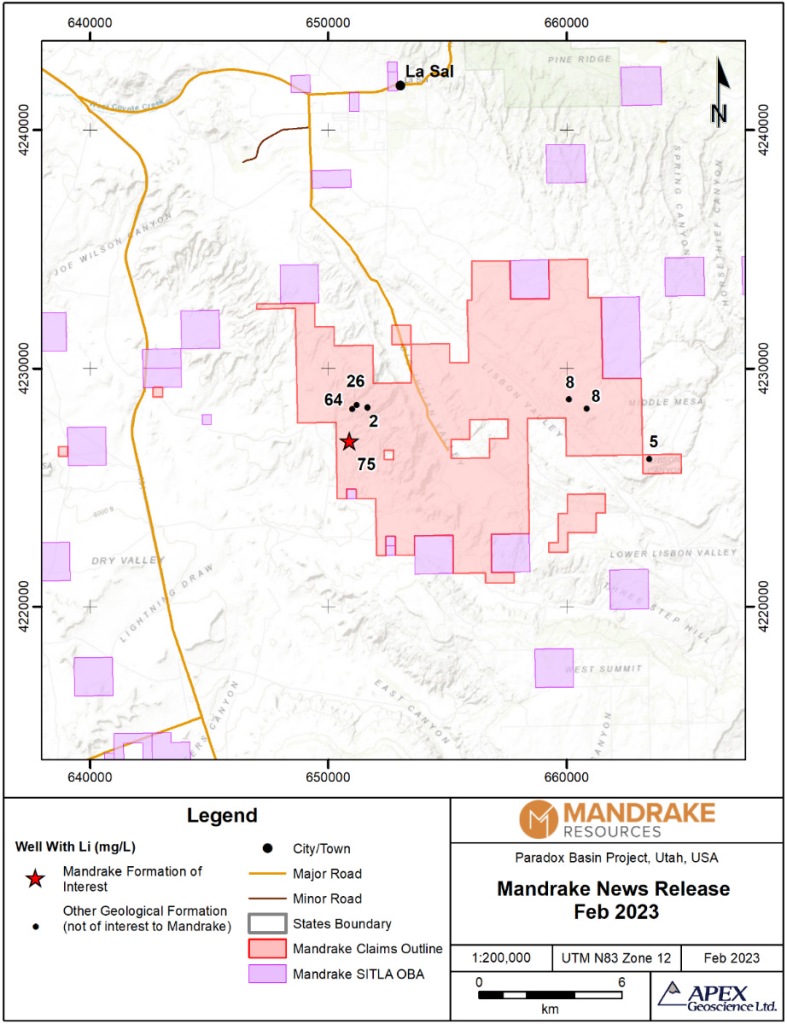

The Lisbon Valley mining claim rush continues: In May, Australia-based Mandrake Lithium filed 217 20-acre placer claims, totaling 4,340 acres, on Bureau of Land Management parcels in the Lisbon Valley in San Juan County, Utah.

That’s a lot of land, but is only makes up a small piece of the company’s 88,000-acre proposed Utah Lithium Project, comprised of 2,700 BLM claims and a 34,670-acre swath of Utah School Institutional and Trust Lands Administration parcels. The main block of acreage lies south of the town of La Sal, with the SITLA lands scattered about the general vicinity.

In a press release, Mandrake Resources Managing Director, James Allchurch crowed: “Mandrake has now secured, at a very little cost, over 80,000 acres prospective for lithium brines in the Paradox Basin, Utah, confirming the acquisition of a potentially world-class lithium project.” It appears that they’ll be using old oil and gas wells and perhaps drilling new wells to extract the lithium.

The Lisbon Valley, which lies east of Canyonlands National Park between Moab and Monticello, has long been targeted by mining and oil and gas drilling companies. It was where Charlie Steen established his Mi Vida uranium mine, making him a millionaire, sparking a regional prospecting frenzy and turning Moab into a boomtown, if only for a little while. It’s drawing uranium and copper mining once again, along with various companies staking claims for lithium mining. Also holding large blocks of claims in the Lisbon Valley are Boxscore Brands and MGX Minerals Petrolithium.

Mandrake’s project, were it ever come to fruition, would be the largest in the Lisbon Valley by far, acreage wise. But they still have a long ways to go before anything actually happens.

They may get a bit of help from a proposed land swap between SITLA and the U.S. Interior Department aimed at making Bears Ears National Monument whole. SITLA will hand over 130,000 acres of its lands within Bears Ears National Monument, in addition to 30,000 acres of state lands elsewhere in Utah, to the federal government. In exchange, the BLM will give SITLA 163,000 acres from around Utah, including 52,000 acres in San Juan County, a good chunk of it in the Lisbon Valley.

Regulations on state land are likely to be even looser than those on federal land. So the land swap should benefit Mandrake and other companies looking to mine the Lisbon Valley.

In other mining claim news …

Freeport-McMoran Exploration Corp. files 89 20.66-acre lode claims in southwestern New Mexico totaling 1,838 acres. The claims are in a small mountain range just south of I-10 and west of Cotton City right along the Arizona line. Freeport-McMoran is a huge mining company that typically focuses on copper and molybdenum.

Majuba Mining files 19 20-acre claims near Lordsburg, New Mexico, (and just north of the aforementioned Freeport-McMoran claims) in a dry lake bed. They appear to be expanding their holdings here, though it’s not clear what they intend to mine (though the alkali flats could point to lithium). I can’t find much on Majuba Mining except that they seem to have mining claims in Nevada and were in a lawsuit a few years back over paying maintenance fees on claims.

Western Cobalt LLC, with offices in Sandy, Utah, files 127 20.66-acre lode claims in Tooele County, Utah, between Utah Lake and Dugway totaling 2,624 acres. This is outside our usual geographic focus, but we noticed it for the large size of the property as well as the fact that it’s made by a company with “cobalt” in its name. Which leads us to think maybe they’re planning on mining cobalt, which is used in electric vehicle and grid-scale batteries. This is notable because the nation’s only large-scale cobalt mine recently opened in Idaho — and then promptly shut down (before producing anything) due to decreasing prices of the metal.

These projects and more can be found on the Land Desk Mining Monitor Map, updated regularly.

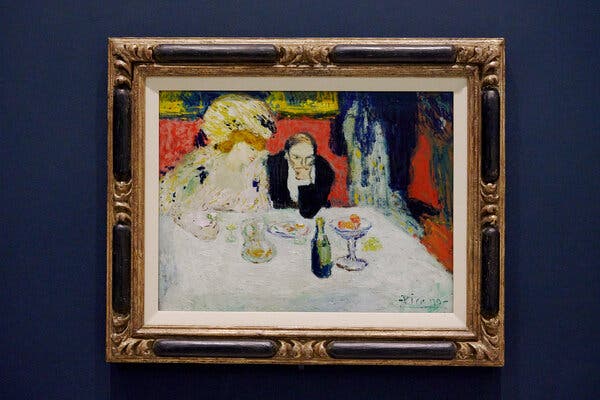

PICASSO BECOMING PICASSO ~ NYT

.

A small, exquisite exhibition at the Guggenheim shows how the City of Light transformed the 19-year-old Spanish artist. One painting says it all.

May 11, 2023

Some celebrations are fleeting, others bring permanent, tangible results. With “Young Picasso in Paris,” a tiny gem of an exhibition, the Guggenheim Museum has it both ways.

Organized by Megan Fontanella, the Guggenheim’s curator of modern art and provenance, this show is one of over 30 mounted in European and American museums as part of “Picasso Celebration: 1973-2023,” which has been spearheaded by the Musée Picasso-Paris on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the artist’s death. The point seems to be that in the half century since then, the legacy of the 20th century’s greatest artist remains undiminished, continues to influence new generations of artists and still contains mysteries to be discovered by scholars and new technologies.

The Guggenheim show hits all of these marks. The museum has used the celebration as an impetus to continue the analysis (initiated in 2018) and undertake the conservation of its best-known and most beloved Picasso painting: “Le Moulin de la Galette,” of 1900, and to make this beguiling, subtly refreshed work the centerpiece of “Young Picasso.”

As Picasso shows go, it has a distinctive lightness. For one thing it contains only 10 works. But it is also unburdened by the artist’s oppressively unforgettable, often disturbing life story, of which there was as yet not much. It gives us Picasso before he was Picasso, which was in essence Picasso before he knew Paris.

He had traveled there from Barcelona by train with his friend, the Spanish poet and painter Carles Casagemas, in order to visit the Universal Exhibition, which was nearing its conclusion. He wanted to see a painting of his hanging in the Spanish Pavilion. This was “Last Moments” from 1898, which he repainted in 1903 as “La Vie,” a high point of his Blue Period.

But Picasso’s larger mission was to breathe in Paris — the capital of the 19th century in Walter Benjamin’s words — and take a crash course in modern French painting. During the visit he worked hard in studios shared with other artists and often their models. And he voraciously sampled everything the city had to offer a frighteningly talented, ambitious, curious, sociable yet provincial young artist. He visited museums to see older art and galleries for the latest thing. He partook of the glamorous bohemian nightlife in cafes, cabarets and dance halls, of which “Le Moulin de la Galette” was the most famous.

And he got to know people, initially Spanish artists and writers, some of whom he had known in Barcelona, and a widening circle of Parisians as he learned French.

At the Guggenheim, “Le Moulin de la Galette” occupies pride of place in a large gallery painted in a slightly cool (in temperature) dark blue. Reigning in magnificent solitude from one of the longest walls, this seductive wide-angle view depicts a dance hall full of beautiful people — elegantly turned-out women and top-hatted men — who dance, drink and exchange pleasantries or gossip while their eyes slide away, perhaps seeking out the very topic of discussion. It is relatively quiet — Picasso would also paint cancan dancers, but not now — a suave, sophisticated crowd painted by an artist who understood its fashions, body language and interpersonal connections perfectly.

It also shows him mulling over the painting styles of his elders — Renoir, Toulouse-Lautrec, the Swiss born illustrator Théophile Steinlen in particular. I might add a soupçon of Seurat, to account for the smooth unruffled Classical forms of the dance hall’s clientele.

The prevailing darkness, in which the men’s black coats alternate with the subtle colors and fabrics of the women’s garments, owes something to Picasso’s love of Velázquez and Goya. But the colors that bloom from its shadows brighten throughout several of the other paintings: in the coarse pointillism of “Woman in Profile” and “Courtesan With Hat,” and the flat colors of “The Diners” — especially the red banquette on which the mismatched couple are seated. In the parade of “The Fourteenth of July” — the only glimpse of daylight here — tossing and turning strokes of red, white and blue suggest a riled Impressionism.

The completeness and complexity — the amazing growth spurt — of “Le Moulin de la Galette” cannot be underestimated. It is one of the first paintings Picasso completed in Paris — the masterpiece of this initial two-month transformative immersion. It was also the first Picasso to enter a French collection, selling quickly through the art dealer Berthe Weill — whose role in discovering Picasso is often overlooked — to the progressive publisher and collector Arthur Huc.

“Le Moulin de la Galette” has been off view since November 2021. Its painstaking conservation was led by Julie Barten, the museum’s senior painting conservator, with input from Fontanella. Not unlike doctors, the conservator’s oath is do no harm, or more precisely nothing that cannot be reversed. They initiate a project only after reaching a consensus based on discussions with colleagues — art historians, curators and conservators from their own and other museums.

![The Rōbert [Cholo] Report (pron: Rō'bear Re'por)](2016/10/cropped-cropped-roberrepor-site-logo2-e1479848562926.png)