For the nineties, the celebrated Beat rebel advocates “wild mind,” neighborhood values and watershed politics. “Wild mind,” he says, “means elegantly self-disciplined, self-regulating. That’s what wilderness is. Nobody has a management plan for it.”

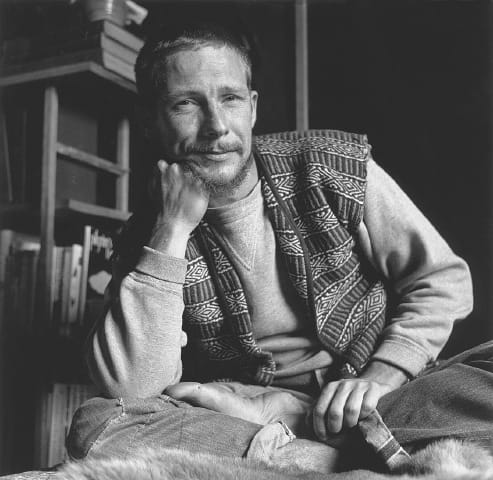

Asked if he grows tired of talking about ecological stewardship, digging in, and coalition-building, the poet Gary Snyder responds with candor: “Am I tired of talking about it? I’m tired of doing it!” he roars. “But hey, you’ve got to keep doing it. That’s part of politics, and politics is more than winning and losing at the polls.”

These days, there’s an honest, conservative-sounding ring to the politics of the celebrated Beat rebel. Gary Snyder, though, has little in common with the right wingers who currently prevail throughout the western world.

“Conservatism has some very valid meanings,” he says. “Of course, most of the people who call themselves conservative aren’t that, because they’re out to extract and use, to turn a profit. Curiously, eco and artist people and those who work with dharma practice are conservatives in the best sense of the word-we’re trying to save a few things!

“Care for the environment is like noblesse oblige,” he maintains. “You don’t do it because it has to be done. You do it because it’s beautiful. That’s the bodhisattva spirit. The bodhisattva is not anxious to do good, or feels obligation or anything like that. In Jodo-shin Buddhism, which my wife was raised in, the bodhisattva just says, ‘I picked up the tab for everybody. Goodnight folks…’ ”

Five years ago, in a prodigious collection of essays called The Practice of the Wild, Gary Snyder introduced a pair of distinctive ideas to our vocabulary of ecological inquiry. Grounded in a lifetime of nature and wilderness observation, Snyder offered the “etiquette of freedom” and “practice of the wild” as root prescriptions for the global crisis.

Informed by East-West poetics, land and wilderness issues, anthropology, benevolent Buddhism, and Snyder’s long years of familiarity with the bush and high mountain places, these principles point to the essential and life-sustaining relationship between place and psyche.

Such ideas have been at the heart of Snyder’s work for the past forty years. When Jack Kerouac wrote of a new breed of counterculture hero in The Dharma Bums, it was a thinly veiled account of his adventures with Snyder in the mid-l950’s. Kerouac’s effervescent reprise of a West Coast dharma-warrior’s dedication to “soil conservation, the Tennessee Valley Authority, astronomy, geology, Hsuan Tsang’s travels, Chinese painting theory, reforestation, Oceanic ecology and food chains” remains emblematic of the terrain Snyder has explored in the course of his life.

One of our most active and productive poets, Gary Snyder has also been one of our most visible. Returning to California in 1969 after a decade abroad, spent mostly as a lay Zen Buddhist monk in Japan, he homesteaded in the Sierras and worked the lecture trail for sixteen years while raising a young family. By his own reckoning he has seen “practically every university in the United States.”

As poet-essayist, Snyder’s work has been uncannily well-timed, contributing to his reputation as a farseeing and weatherwise interpreter of cultural change. With his current collection of essays, A Place In Space, Snyder brings welcome news of what he’s been thinking about in recent years. Organized around the themes of “Ethics, Aesthetics and Watersheds,” it opens with a discussion of Snyder’s Beat Generation experience.

“It was simply a different time in the American economy,” he explained when I spoke to him recently in Seattle. “It used to be that you came into a strange town, picked up work, found an apartment, stayed a while, then moved on. Effortless. All you had to have was a few basic skills and be willing to work. That’s the kind of mobility you see celebrated by Kerouac in On The Road. For most Americans, it was taken for granted. It gave that insouciant quality to the young working men of North America who didn’t have to go to college if they wanted to get a job.

“I know this because in 1952 I was able to hitch-hike into San Francisco, stay at a friend’s, and get a job within three days through the employment agency. With an entry level job, on an entry level wage, I found an apartment on Telegraph Hill that I could afford and I lived in the city for a year. Imagine trying to live in San Francisco or New York-any major city-on an entry level wage now? You can’t do it. Furthermore, the jobs aren’t that easy to get.”

The freedom and openness of the post-war economy made it possible for people such as Snyder, Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, Lew Welch and others to disaffiliate from mainstream American dreams of respectability. And as Snyder writes, these “proletarian bohemians” chose even further disaffiliation, refusing to write “the sort of thing that middle-class Communist intellectuals think proletarian literature ought to be.”

“In making choices like that, we were able to choose and learn other tricks for not being totally engaged with consumer culture,” he says. “We learned how to live simply and were very good at it in my generation. That was what probably helped shape our sense of community. We not only knew each other, we depended on each other. We shared with each other.

“And there is a new simple-living movement coming back now, I understand,” he notes, “where people are getting together, comparing notes about how to live on less money, how to share, living simply.”

![The Rōbert [Cholo] Report (pron: Rō'bear Re'por)](https://robertreport.files.wordpress.com/2016/10/cropped-cropped-roberrepor-site-logo2-e1479848562926.png)