A mid-water year update

The water year, which runs from Oct. 1 to Sept. 30, is halfway over. And this is typically about when snowpack levels peak across most basins, with low-elevation areas melting out sooner and higher elevation spots usually accumulating snow for another couple of weeks. So it’s a good time for a mid-water year snowpack update.

I would describe the situation as mixed, which is actually a heck of a lot better than I expected.

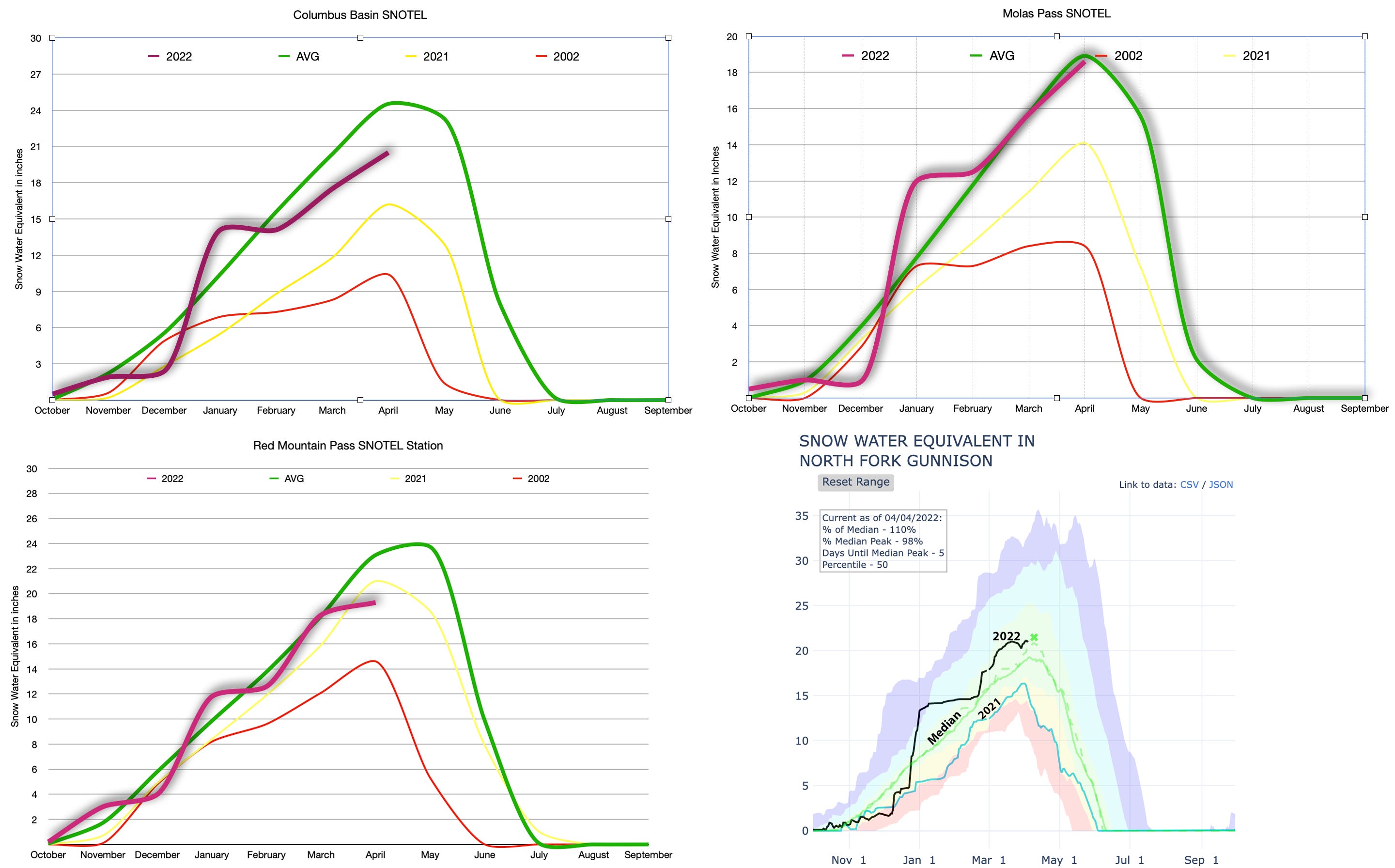

Let’s start with the bad news. When taking a zoomed-out, big-basin-wide view, things look a bit grim. The April 1 snowpack level across 131 SNOTEL sites in the Upper Colorado River watershed — which covers 100,000+ square miles at varying elevations—was at about 80 percent of the period-of-record median for the date. Levels appear to have peaked on March 24, about two weeks earlier than “normal.”

Put another way, the region’s snowpack is no better than last year’s at this time. And that, as you may remember, did not turn out so well. Some Four Corners region farmers never received any irrigation water at all, others got only a small percentage of the usual supply. A lot of folks didn’t even bother planting crops. And Lake Powell’s inflows were only about 4 million acre feet, less than half of the minimum that Glen Canyon Dam operators must send downstream. That explains why Lake Powell shrunk so dramatically over the past year.

As you can see from the above graph, however, the snowpack level isn’t the only factor determining the amount of water that makes it into Lake Powell. The winter and spring of 2002 were far drier than in 2021, for example, but the inflows for the water year were almost the same for both years. Current soil moisture, how rapidly the snow melts, and amount of upstream withdrawals also affect the Colorado River’s flow.

And that’s where some more bad news comes in: In order to keep Lake Powell from sinking too low last summer, the Bureau of Reclamation released extra water from upstream reservoirs, including Blue Mesa, Navajo, and Flaming Gorge. Now Blue Mesa has about half the volume of water as it normally would on April 1 and Navajo is at about 65 percent of normal, meaning more water will have to be withheld to get them back up again, leaving less water for Powell.

McPhee Reservoir is at about the same level as this time last year, when dam operators released a mere trickle from the dam, basically drying up the Lower Dolores River. This year the snowpack is looking a bit healthier. Still, I wouldn’t count on running Snaggletooth any time soon, unless it’s on a bike.

And the good news? While mid-elevation snows melted out rapidly during the end of March heat spell—pulling down snowpack levels across large basins—the high country stayed just cool enough to avoid a mass thaw event. At Columbus Basin, high in the La Plata Mountains of southwestern Colorado, the snowpack is below average for this time of year, but in far better shape than it was a year ago. That bodes well for farmers in the Mancos Valley and on La Plata County’s Dryside, which should get a bigger runoff that lasts longer into the summer. It’s a similar story up on Red Mountain and Molas Passes.

Also, a healthy monsoon last summer bolstered soil moisture levels somewhat, which may mean more of the snowmelt will go to the streams, rather than being sucked up by the parched ground. And in the North Fork of the Gunnison, snowpack levels are above the median, meaning the Paonia and Hotchkiss farmers should be okay this summer.

And…. remember how you revealed your favorite green chile joints and bookstores? Well, they didn’t go into the void. We put them all in our Land Desk Green Chile Atlas! So how about a giant reading and eating road trip?

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~`

.

Now, it’s spillway time!

If you read my impressions from a visit to Hoover Dam, you’ll remember that I ended it with these sentences describing the spillway at the dam (not the dam, itself): “It’s beautiful in the way functional structures can be. And yet, it no longer serves any real function—and never will—except, perhaps, as a reminder of what was.”

When the venerable LA Times environment reporter Sammy Roth tweeted out the description, this was one of the responses:

Okay, well, I’m not sure how it’s “arrogant” to say that a spillway will never be used again, but a subsequent Twitter discussion fleshed out the bigger point he was trying to make: Just as climate change can exacerbate drought, warming can also trigger extremely abundant precipitation, leading to catastrophic flooding a la 1983, which could fill up the reservoirs again and put the spillways back into use. Others piped in, as well, pointing to Lake Oroville in California, which went from nearly empty to overflowing and back to empty over the course of several years.

It got me thinking that maybe I had been too rash in asserting the spillways would never be needed again. After all, anything’s possible: We know that the 1911 Flood sent around 300,000 cubic feet per second or more past the current Glen Canyon Dam site (compared to the 1983 flows of 120,000 cfs), and paleoflood investigations suggest deluges in the distant past have topped out above 600,000 cfs—a Biblical sort of event.

Could a climate change-induced megaflood of this magnitude reverse the effects of a climate change-induced megadrought and fill Powell and Mead back to the brim?

It seems unlikely.

The issue here is one of scale. Lake Powell and Lake Mead are both gargantuan in size. Powell is 186 miles long when full with over 1,900 miles of coastline. It can store nearly 27 million acre feet (af) of water (minus a million or two due to siltation). Contrast that to Lake Oroville, with its relatively minuscule 3.5 million acre feet of capacity.

Powell currently has less than 6 million acre feet in it, leaving 20 million acre feet of empty storage that needs to be filled before water would reach the spillways. Lake Mead’s numbers are similarly huge.

Now, the monster flood of 650,000 cfs would dump 1.3 million acre feet of water per day into the reservoir. So, you’d need two weeks of this to fill up Powell—and Lake Mead would still have 20 million acre feet of unused capacity, meaning you’d need another two weeks of deluge to fill it up. Megafloods usually don’t last that long—the 1911 Flood brought up river levels for several days, not weeks (and Colorado river flows for the entire year were unremarkable). And besides, 650,000 cfs isn’t going to sneak up on the dam operators. They’d see it coming and start releasing water from the reservoirs ahead of time, obviating the need to use the spillways.

Conclusion: A sudden megaflood is not going to cause either Mead or Powell—and certainly not both of them—to overflow.

But what about a string of really wet years, when record-setting snowfall is followed by torrential summer rains? We know this is possible, because it’s exactly what happened in 1983 through 1986, the last time the spillways were used. We also know, from streamflow reconstructions back to the 8th Century, that the wet and wild 1980s were not entirely unprecedented. They were, however, an anomaly, and they are among the wettest four consecutive years on record.

So, let’s assume a repeat. Would that fill the dams to overflowing and put the spillways back to use? Perhaps.

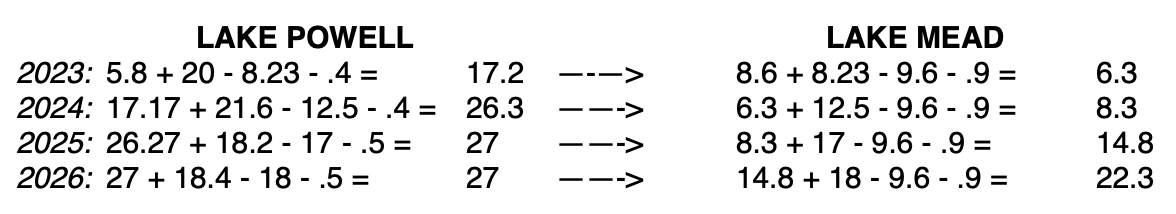

Here are the numbers as of March 30:

- Lake Powell Current storage: 5.8 million acre feet (MAF)

- Full capacity: 27 MAF

- Minimum annual release: 8.23 MAF

- Annual evaporation: .4 MAF

- Lake Mead current: 8.6 MAF

- Full capacity: 28.2 MAF

- Minimum annual release: 9.6 MAF

- Annual evaporation: .6 MAF

- Las Vegas withdrawal: .3 MAF

These were the actual inflows into Lake Powell during the super soaker years from 1983-1986, also known as the only time the spillways at Glen Canyon and Hoover Dams were actually used. It didn’t go so well, but we’ll get to that in a minute.

- 1983: 20 MAF

- 1984: 21.6 MAF

- 1985: 18.2 MAF

- 1986: 18.4 MAF

To put this in context, consider inflows during the four biggest water years of the last two decades:

- 2011: 16.3 MAF

- 2008: 12.4 MAF

- 2019: 11.7 MAF

- 2005: 11.4 MAF

And, just to give you an idea of the dismal state of the Colorado River currently:

- 2021: 4.03 MAF

Glen Canyon Dam operators are required to send at least 8.23 MAF downstream to Lake Mead each year, but usually only go above that when Powell gets close to full and “equalization” kicks in—it’s basically a “fill Powell first” philosophy. The following Glen Canyon release numbers are guesses based on that. Of course, once Lake Powell is full, then releases would equal inflows.

The equation, then, is:

Begin Water Year Storage + Inflows – (evaporation+withdrawals) = End WY Storage

So, at the end of the nearly unprecedented string of wet years, Lake Powell would be full but Lake Mead still would need another 6 million acre feet of water before the spillways could be used.

Let’s just say I’m feeling better about my spillway “never again” comment.

There is another possible scenario: Four years of giant snow/water years followed by the monster megaflood—the double whammy. That certainly would fill up both Powell and Mead and could lead to a 1983 situation all over again, or worse.

But that doesn’t necessarily mean the spillways would be utilized again. In fact, dam operators will do everything they can to avoid it because they really aren’t intended to be used. In 1983 it wasn’t the big water that forced the spillways into use, it was the dam operators’ failure to prepare for the sudden runoff by releasing enough water beforehand. And that stemmed from faulty weather forecasting.

When the runoff did hit the already full reservoir, it caused the water to spill into the spillways, which are actually tunnels through the cliffs on either side of the dam. A phenomenon called cavitation occurred, in which vapor bubbles in the water collapse, sending shockwaves through the tunnels. That tore huge gouges into the concrete lining and then the rock, which in turn threatened the dam, itself. Plywood extenders were added to the top of Glen Canyon Dam’s spillway gates to stop the water from entering them.

So, even in the extraordinarily unlikely event of a double whammy 1983 water year + a megaflood, dam operators will be ready for it. So, I’m standing by my assertion as rash as it may be: The spillways on both Glen Canyon and Hoover Dams are obsolete, except maybe as extreme skateboarding chutes.

![The Rōbert [Cholo] Report (pron: Rō'bear Re'por)](https://robertreport.files.wordpress.com/2016/10/cropped-cropped-roberrepor-site-logo2-e1479848562926.png)