.

.

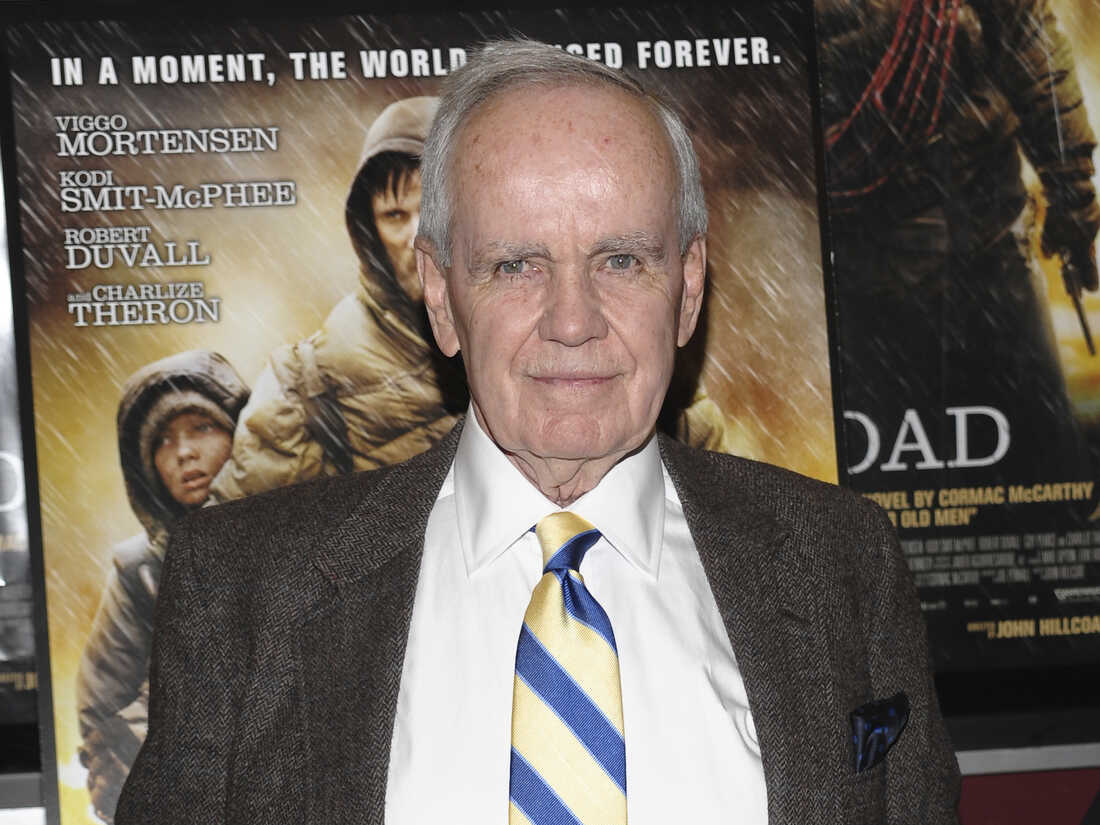

Now that 89-year-old Cormac McCarthy is widely hailed as one of our greatest living authors, it’s hard to remember that when he published “All the Pretty Horses” in 1992, few people were waiting for it. Although McCarthy had been writing for decades, his work — including the epic western “Blood Meridian” — was still largely the secret treasure of a small retinue of intense fans.

Inconspicuousness suited the author just fine, but like every fragile thing in the McCarthy universe, it would soon die.

“All the Pretty Horses,” the first volume of his Border trilogy, flirted with the bestseller list for months and then went on to win the National Book Award for fiction. McCarthy did not attend the New York ceremony to accept his prize, but the damage was done: He was becoming famous.

Nothing, though, could have prepared the author for the clamorous success of “The Road,” which extended his apocalyptic themes to the literal end of civilization. This lean story about a father and his little boywalking through a hellscape mesmerized — and terrified — readers. The novel won a Pulitzer Prize, which made perfect sense, but it also won a spot on Oprah’s Book Club, which felt like a rip in the space-time continuum because it meant McCarthy would, for the first time, give an interview on TV. There, finally, we saw the shy, gentle writer, not so much disdainful of public adoration as inert to it.

For the last 16 years, McCarthy’s swelling fan base has been circling, picking at crumbs of information about his next project. This month, the moment of unveiling has arrived with a tempest of publicity that’s sure to draw in even more readers.

Prepare to be baffled.

“The Passenger” exhibits McCarthy’s signature markings, but it’s a different species than we’ve spotted before. In these pages, the author’s legendary violence has been infinitely reduced to the clash of subatomic particles.

Bobby Western, the novel’s contemplative, haunted hero, works as a salvage diver. We meet him at 3:17 a.m. off the Gulf Coast. He and a small crew are examining a private jet resting on the ocean floor. After his partner cuts open the door with an underwater torch, Western swims into this fresh tomb:

“He kicked his way slowly down the aisle above the seats, his tanks dragging overhead. The faces of the dead inches away,” McCarthy writes. “The people sitting in their seats, their hair floating. Their mouths open, their eyes devoid of speculation.”

A few minutes later, back in the inflatable boat, Western shakes his head. “There’s nothing about this that rattles right.” The bodies look unaffected by a crash. And the pilot’s flight bag and the data box are missing from the cockpit.

Western’s partner asks, “You think there’s already been somebody down there, don’t you?”

“I don’t know.”

For several days, Western hears nothing in the news about a jet crashing into the gulf. Then two men with badges appear at his apartment in New Orleans. They want to know how many bodies he saw in the plane because “there seems to be a passenger missing.”

McCarthy has assembled all the chilling ingredients of a locked-room mystery. But he leaps outside the boundaries of that antique form, just as he reworked the apocalypse in “The Road.” Indeed, “The Passenger” sometimes feels more reminiscent of Franz Kafka’s “The Trial.” Western knows he’s suspected of something, but he’s not told what. The two men who repeatedly question him never drop their formal politeness — never flash a bolt gun like Anton Chigurh in “No Country for Old Men” — but Western knows that his life is in danger and that he must run.

First, though, he ruminates, and that sustained rumination creates a very different novel than the heart-thumping thriller the opening suggests. Instead, we’re drawn deeper and deeper into the troubled soul of Bobby Western. His father worked with Robert Oppenheimer to create the first atomic bombs, and Western still labors under a kind of genetic guilt for unleashing such horror on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

In a futile attempt to come to terms with that legacy and other ghosts, Western chats with a collection of barflies who seem to have wandered in from other classics. There’s Debussy Fields, a trans woman doing an extravagant imitation of Brett Ashley from “The Sun Also Rises.” And there’s Sheddan, who sounds like he never recovered from playing Falstaff in a college production of “Henry IV.”

“A pox upon you,” he says. “You see in me an ego vast, unstructured, and baseless. But in all candor I’ve not even the remotest aspirations to the heights of self-regard which the Squire commands.”

The style — a mingling of profound contemplation and rapid-fire dialogue, always without quotation marks and often without attribution — is pure McCarthy. But so is the irritating tendency toward grandiosity. “Evil has no alternate plan. It is simply incapable of assuming failure,” he writes. “The last of all men who stands alone in the universe while it darkens about him. Who sorrows all things with a single sorrow. Out of the pitiable and exhausted remnants of what was once his soul he’ll find nothing from which to craft the least thing godlike to guide him in these last of days.”

The Book of Job might get away with language like that, and maybe Melville can pull it off on a particularly bleak day, but here it risks sounding comically overwrought.

Brooding and good-looking, Western “is sinking into a darkness he cannot even comprehend.” Women want to save him; men want to befriend him. And why not? Working as a salvage diver sounds exotic and cool. He earned a scholarship to study physics at Caltech. He used to be a racecar driver in Europe, and he still roars around in his Maserati. (He thinks of the trident symbol on the car’s grill as “Schrödinger’s wavefunction.” Sure.) And — yes, seriously — he lives off thousands of gold coins he found buried under his dead grandmother’s house.

But on the non-sexy side of the ledger, Western is still pining for his little sister, Alice, a mathematical prodigy who wanted to bear his baby. Apparently, during her brief, tumultuous life, they shared more than a love of complex equations.

(That shuffling sound you hear is Hollywood directors tiptoeing away.)

One of Western’s friends tries to cast this incestuous relationship in terms of a Greek tragedy, but McCarthy suggests it’s a geek tragedy. Throughout the novel, we’re subjected to intercalary chapters about Alice and a menagerie of Vaudeville freaks who inhabit her psychotic hallucinations. Chief among these figures is the Thalidomide Kid, who torments her in conversations so bizarre and relentless that I began to wish I were on that plane at the bottom of the gulf.

Weirdly, in early December, McCarthy is releasing a related short novel called “Stella Maris” — the name of a psych hospital — which is composed entirely of dialogue between Alice and a doctor. I doubt there are more than a few hundred people in the country who can follow Alice’s freewheeling allusions to theoretical physics and advanced mathematics — certainly her doctor can’t. But the bigger mystery is why this material, which depends entirely on “The Passenger,” is being published separately.

On the other hand, maybe it’s a mercy. “The Passenger” is already burdened by a reference to space aliens, a conspiracy theory about the Kennedy assassination and enough scientific arcana to choke a Higgs boson. McCarthy can’t go long without referring to the work of Dirac, Pauli, Heisenberg, Einstein, Rotblat, Glashow, Teller, Bohm, Chew, Feynman and other scientists. Unless you majored in physics, your string theory is going to get badly tangled up with your Yang-Mills. This is the kind of novel in which people wonder, “What happened to Kaluza-Klein?”

Later, we’re told that a Swiss mathematician and physicist named Ernst Stueckelberg “worked out a good bit of the S-Matrix theory and the renormalization group.”

I’m happy to hear that worked out, but I still have no idea what the hell it means.

When McCarthy descends from Mount Olympus and writes in his close, precise voice about Western carving out the ordinary activities of his day, the novel suddenly hums with genuine profundity. But many pages strain self-consciously to explore Big Ideas about the Nature of Reality. The explanations are so cursory that we never get to see the light — just the shadows on the cave wall. Unlike the cerebral novels of Richard Powers, which create the illusion that you might actually understand neuropsychology, genetics or artificial intelligence, “The Passenger” casts readers into a black hole of ignorance.

Near the end, a friend tells Western, “We still dont know what this is about.”

Get used to it, man.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

.

After 16 years, author Cormac McCarthy gifts two new novels to readers ~ NPR

~~~ LISTEN TO THE 7 MINUTE INTERVIEW ~~~

Devoted Cormac McCarthy fans who have been waiting 16 years for new work from the renowned American writer are in for a surprise.

The Passenger, by Cormac McCarthy

Knopf

The reclusive author’s two new interconnected novels — being released on Oct. 25 and Dec. 6, respectively — are hard to categorize.

The first book, The Passenger, opens with a mysterious plane crash at sea that’s searched by a neurotic salvage diver who’s obsessed with his sister. The entire second book, Stella Maris, consists of erudite conversations between that sister, who happens to be a mathematical genius, and a therapist in the psychiatric hospital where she’s committed herself.

By all accounts, McCarthy has been working on them for at least four decades.

“Eight years ago, it was so cloak-and-dagger that we were working on these books because McCarthy fans are rabid and any whiff of there being new books is going to be huge news,” says Jenny Jackson, executive editor at Knopf, who began working with him in secret in 2014. “We’d walk down the hall and hand off manuscripts in person. And I wasn’t telling anyone what we were working on.”

For the interview, Jackson comes to the Napoleon House, a venerable watering hole in the French Quarter of New Orleans — where McCarthy lived as a young, penurious writer. The protagonist in The Passenger is a troubled commercial diver named Bobby Western who frequents the Napoleon House for rambling discourses with eccentric buddies.

“At the beginning,” Jackson says, “there’s this big cast of boisterous characters and they’re all working as divers and having drinks together and going out to restaurants. And then at the end they’re each kind of on their own singular journey.”

Neither of these two new books contains the savagery and bloodletting McCarthy readers have come to expect. There’s less action overall and more dialogue. Readers may wonder if McCarthy has mellowed now that he’s 89 years old.

The breathless blurb on the back cover of The Passenger reads: “A sunken jet. Nine passengers. A missing body…A salvage diver pursued for a conspiracy beyond his understanding.” But this is not a fast-paced crime thriller like No Country For Old Men, which became an Oscar-winning screenplay for the Coen Brothers.

The Passenger starts out as a who-dun-it but then veers into Bobby’s metaphysical musings.

“When you’re Cormac McCarthy and you’ve writtenThe Road, what on earth can you do next except tackle God and human consciousness?” Jackson asks.

The Road is McCarthy’s best-selling last novel, released in 2006, about a father and son’s harrowing journey among latter-day cannibals in a post-apocalyptic landscape. It won a Pulitzer.

McCarthy described the genesis of The Road in his only broadcast interview, granted to Oprah Winfrey in 2007. He says he happened to be in El Paso with his young son.

“I just had this image of these fires up on the hill and everything being laid waste and I thought a lot about my little boy. And so I wrote these pages and that was the end of it. And then about four years later I was in Ireland and I woke up one morning and realized it wasn’t two pages, it was a book.”

The new paired books are more dense than dark. Notably, they reflect McCarthy’s love, and thorough understanding, of theoretical physics and mathematics. He has said, in his few interviews, that he seeks out the company of scientists at the Santa Fe Institute near his home in New Mexico.

Determined McCarthy fanatics have found advanced copies of the books, and they have provoked strong reactions. Some McCarthy aficionados were interviewed in September at a Cormac McCarthy conference in Savannah, Georgia.

“The novels explore all these aspects of human mental behavior. I think they’re just marvelous,” says Diane Luce, former president of the Cormac McCarthy Society.

And Bryan Giemza, literature professor at Texas Tech University, says: “In some ways, they’re flawed. They are likely to be inscrutable to a lot of people. Let’s just say they’re not my favorite novels.”

A third early read, Lydia Cooper, English professor at Creighton University, says: “They are brain teasers, but they’re also really compelling. The characters are really rich and fascinating. I think people are going to love them or hate them.”

One of the organizers of the conference in Georgia was Stacey Peebles, an English professor who teaches a McCarthy course at Centre College, and is editor of the Cormac McCarthy Journal.

“I’ve had students coming by my office. They say, ‘Are you going to teach the new ones? I’m so excited.’ “

Peebles has also read both new books.

“We’ve been waiting for these a long time,” she says. “There’s always the possibility that you’re going to read something new and be disappointed. But I read ’em once. I read ’em again. And I’ll probably keep reading ’em. I mean, all of McCarthy’s works have sentences that’ll just stop you cold, but these have a lot of those.”

Here’s one of those sentences, from The Passenger (you can read a longer, exclusive-to-NPR excerpt from Stella Maris here):

“God’s own mudlark trudging cloaked and muttering the barren selvage of some nameless desolation where the cold sidereal sea breaks and seethes and the storms howl from out of that black and heaving alcahest.”

McCarthy — who still composes on a manual typewriter — is considered one of the greatest and most influential writers in the English language.

“I began to notice fairly early on that a lot of these students were writing like Cormac McCarthy,” says Texas novelist and historian Stephen Harrigan, who taught a fiction writing course at the Michener Center for Writers at the University of Texas at Austin. He recalls with a chuckle, “They were writing with strange locutions like, ‘He rode isolate into the darkling plain.’ That kind of language. And this Old Testament archaic usage creates a kind of spell, particularly for young writers.”

The McCarthy spell is about to be cast again, and not just for readers but for researchers.

Cormac McCarthy’s literary papers are archived in a locked cabinet in the Witliff Collections at Texas State University in San Marcos.

“It’s about a hundred boxes of Cormac material that we have here,” says Steve Davis, literary curator at the Witliff, as he rolls open the cabinet. “His collection begins with his first book, Outer Dark,” and it ends with early drafts of The Passenger.

The last box has been restricted for 15 years, since the Witliff acquired McCarthy’s coveted papers, and McCarthy scholars have already been lining up to delve into it. The final box will be opened the same day The Passenger goes on sale — but Davis offered a sneak preview.

“This is the box for the new novel, The Passenger,” he says, “and we’re gonna pull out this first big folder which says, ‘The Passenger, old first draft. Typescript and photocopied pages, heavily corrected in pencil.'”

Perhaps the contents of this box will reveal how Cormac McCarthy’s challenging new novels evolved, and why he wrote them.

![The Rōbert [Cholo] Report (pron: Rō'bear Re'por)](https://robertreport.files.wordpress.com/2016/10/cropped-cropped-roberrepor-site-logo2-e1479848562926.png)