.

A look at a sacred land ravaged by coal mining

| JONATHAN P. THOMPSONJAN 6 |

Each day, thousands of travelers drive along the west flank of Black Mesa in northern Arizona on their way to Flagstaff or Monument Valley or somewhere. Some may wonder about the giant concrete structure jutting up from the sage beside the road, but most passers by surely remain oblivious to the significance of the landform or the destructive and exploitative history that has played out on it for more than a half century.

Black Mesa is home to two massive coal mines, the Black Mesa Mine and the Kayenta Mine. The former fed the Mojave power plant, which shut down in 2005, while the latter provided fuel to the Navajo Generating Station, which closed and stopped spewing greenhouse gases and sulfur dioxide and other pollutants in 2019. The mines, both operated by Peabody, are also permanently idled.

In July, I turned the trusty old Silver Bullet off of Highway 160 onto Route 41 and made the steep climb up the Mesa’s face, pulling off at a turnout just as I reached the top, surprised at how much elevation I’d already gained. Sandstone and sage and piñon-juniper forests unfurled before me, with the horizon line punctuated by the dark hump of Navajo Mountain. The air was clearer than I’d seen it in a long time.

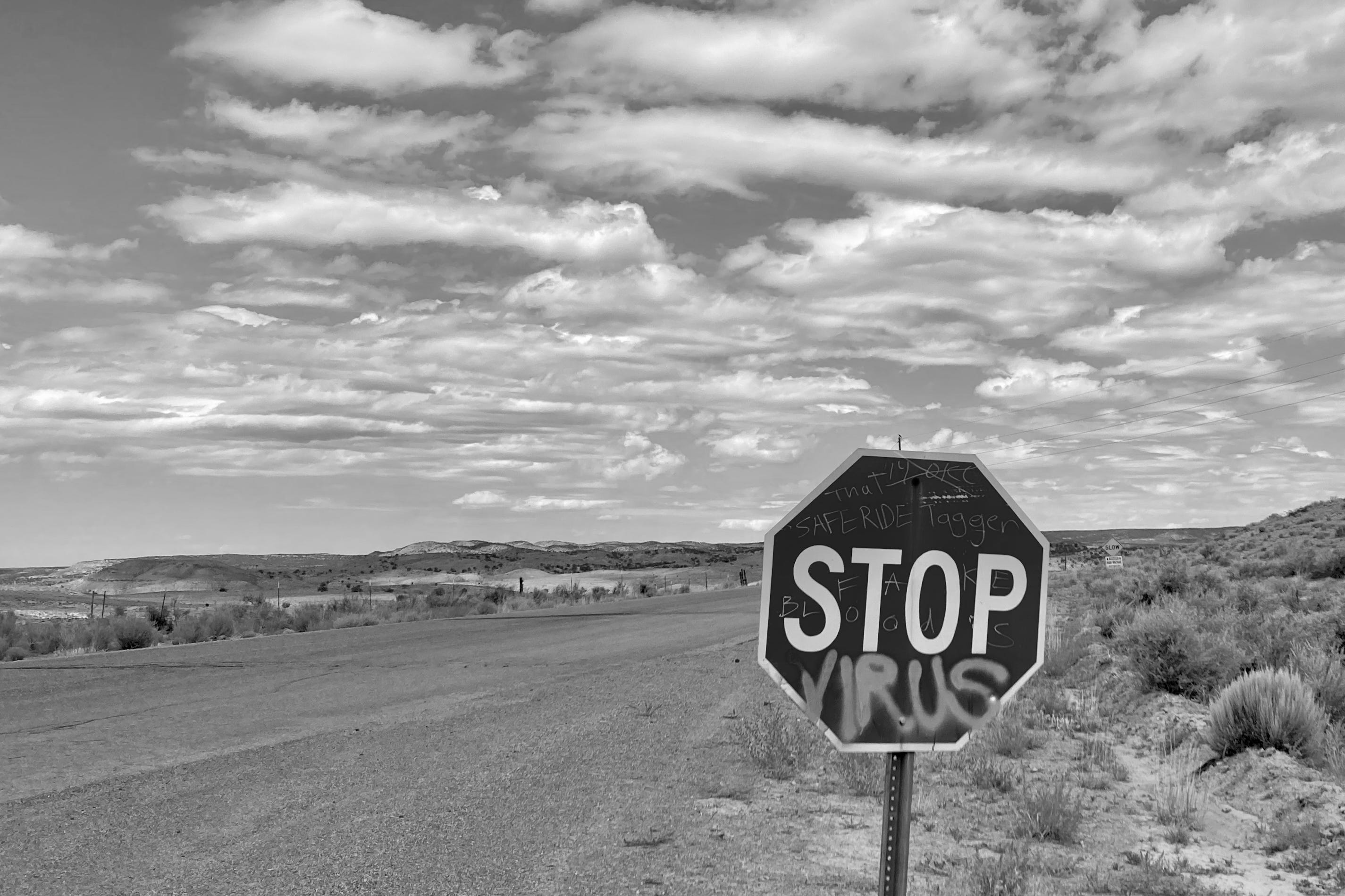

I continued eastward onto the Mesa along the oddly wide, yet mostly empty asphalt road. There was something surreal about the big, weathered signs warning of explosives and blasting and large trucks and the crumpled pieces of machinery scattered about randomly combined with the silence and lack of perceptible activity.

When Peabody was ready to began mining on Navajo and Hopi land on Black Mesa in the 1960s, the Hopi Tribe hired prominent Western attorney John Boyden to negotiate a deal. What they didn’t know is that Boyden was also on Peabody’s payroll at the tiime. So it’s no surprise that both the Navajo Nation and the Hopi Tribe got the short end of the stick in the negotiations, receiving just 2 to 6 percent royalty for the coal, an amount that was finally increased to the still-below-standard rate of 12.5 percent in 1984.

Peabody forced families to relocate, destroyed grazing land, dried up springs and wrecked ancestral Hopi shrines and other sites. The Black Mesa archaeological project identified 2,500 cultural sites dating back thousands of years, many of which were destroyed by the blasting and the draglines.

The sky during my visit was dappled with clouds which cast crazy shadows across rolling grass-covered hills that stretched to the horizon. I guess if you didn’t know what was supposed to be there you might find it kind of pretty. But look more closely and you’ll see that it’s acre after acre of scar tissue, former forests and ecosystems and habitat that had been gouged and blasted apart and stripped of the coal before being being “reclaimed” and revegetated. The vastness of these lands is mind-blowing.

In between these rolling hills are the more recently excavated parts of the Kayenta Mine, which are still gaping, open wounds three years after the mine closed. About 350 people lost their jobs when the mine closed. More than half of them could have stayed on the job if Peabody had committed itself to fixing and healing and restoring the land. Instead, they are haltingly proceeding, appearing to do only what is required, if even that. For more than a half century Peabody took and took and took from the land and the people, enriching corporate shareholders and executives, and fueling the Southwest urban growth machine with cheap, dirty power. The tribal governments grew dependent on the royalty and lease revenues and the communities came to rely on the relatively high-wage, if dangerous, jobs.

Now Peabody — which raked in $799 million in profit during the first nine months of 2022 — is simply abandoning the place and the people, leaving them with nothing but wounded land and diminished groundwater. Now another company is proposing once again to exploit Black Mesa for energy, this time by developing a massive pumped hydropower energy storage facility.

When I reached a high point I pulled off the road again, got out of my car, and sat on a rock and listened to the wind. To the south, curtains of rain hung delicately from bruise-colored clouds. It looked as if the Hopi corn fields were getting some moisture at last.

![The Rōbert [Cholo] Report (pron: Rō'bear Re'por)](https://robertreport.files.wordpress.com/2016/10/cropped-cropped-roberrepor-site-logo2-e1479848562926.png)